Thank you all for coming tonight, and thank you especially to Fellene and Ed for inviting me to give this talk. This year has been incredibly challenging for me, as I’m sure it has been for you all, and it means so much to be able to share my work with you all. While I’ve really struggle to define the term “community” in thinking about community-centered approaches to our work, two things really resonate for me - that these are people who see you, who are invested in your success, and who you are accountable to. I feel all of these things about the CHIFOO community and the greater community of designers, researchers, technologists and thinkers here in Portland, and I am so grateful to be a part of it.

To begin, I’d like to acknowledge a few things, and situate myself and this work in the present moment and context.

First, I’d like to acknowledge that as we gather here tonight as part of the greater Portland design community, that we do so as part of a legacy of colonialism and illegal occupation. The Portland Metro area rests on traditional village sites of the Multnomah, Wasco, Cowlitz, Kathlamet, Clackamas, Bands of Chinook, Tualatin, Kalapuya, Molalla, and many other tribes who made their homes along the Columbia River …” (Portland Indian Leaders Roundtable, 2018)

While the practice of acknowledging the land has become increasingly commonplace in the last few years (something I enthusiastically support), I’d like to extend this beyond an acknowledgement gesture and use this as a place to begin our inquiry tonight.

Last month, I was fortunate to take a trip with my family to Lopez Island in Washington. I first visited the San Juan Islands nearly twenty years ago, and I still feel incredibly lucky to visit and to live in this part of the world around such breathtaking natural beauty. Over the past few months, along with my daughter, I’ve spent some time fishing and clamming as a way to try and spend time outside and away from screens, and to connect with each other and the world around us.

For the non-anglers out there (I personally had not held a fishing pole for over a decade before last year), I want to stress that fishing is a complex art that combines technical knowledge (I had to watch a lot of YouTube videos in order to re-learn how to tie knots) , data gathering, observation and lots of affective work. I’ve found it a deeply humanizing activity and not a particularly materially rewarding one, but nonetheless, found such grace in it, not to mention a new kind of connection to the environment.

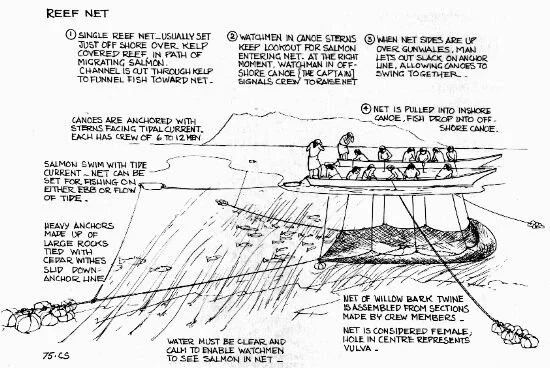

Off the trail in a park last week, I saw an interpretive sign that floored me, it still does, detailing how the Coast Salish peoples had used the site I was standing on dating as far back as 1000 BCE. That they’d developed reef netting practices used to harvest salmon over the course of three thousand years.

It is so humbling to realize how limited your purview of history is, and also to be reminded, on a very basic level, that we all want the same things, and that many of those things are really not mine, or yours, to own. That we, as community and as individuals, have borrowed and stolen a lot of things that we never had any right to. So I want us all to consider tonight, how can we learn, and re-learn to live together and work together in ways that start to repay this huge debt?

Since the shift to work and school from home in the spring, I’ve found that taking bike rides and walks in the park has been incredibly valuable for my well being. I’m fortunate to live close to Mount Tabor, and have found hope and inspiration on the trails there, listening to bird songs and looking up at tall trees.

But the recent police murders of Ahumaud Arbery, a runner and just last week, Dijon Kizee, a cyclist, serve as a very stark reminder that these things - connection with nature, freedom to exist in public spaces, are very inequitably distributed in our society, and often controlled violently. Once again, what have we borrowed and stolen? What have we lost?

So next, I want to state unequivocally that Black Lives Matter, and to call attention to the folks we have lost in the past few years to police violence. In particular, I want to call out George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and from our local community, Kendra James, Quanice Hayes, Patrick Kimmons. This is only to scratch the surface.

Lastly, I also want to acknowledge the losses that we have all experienced as a result of COVID-19 crisis. In May, I lost a member of my family to COVID-19 and even now, it feels hard to believe. I know that many of us have lost loved ones, and had our lives upended. Many of us have lost work, many of us (myself included) have lost access to childcare and other supports that enable us to do our work.

Right now there are a lot of headlines about how bad this crisis is for mothers and other caregivers in their careers. And I know that my career has been impacted, and this will change the course of my work and life. (In mid-July, I left a job at a big tech company because working from home and having no outside childcare was making me feel like a burnt out husk of a person.) But I’m also hopeful that by adapting, by working with others around me, by building connections with neighbors and in embracing change and all it means, that we can help shape the futures we want to live, something I think we’ve been putting off for too long or waiting for others to do for us.

This is a time when it is impossible to carry on as usual, and any attempt to do so reveals how deeply racism, classism, sexism and other forms of oppression have been baked into the systems and institutions we navigate every day. Moreover, for me personally, along with a deep sense of loss, I feel a new urgency and sense of possibility for uprooting injustice and building abolitionist practices in my work and life.

You may have witnessed the Milwaukee Bucks’ strike, which brought sports at a global level to a halt and showed the power of solidarity at work. While there probably aren’t any professional athletes here tonight (although you never know in Portland!), I want to argue that we all hold this same power, and that we can stop and demand changes in our workplaces, our communities, and the world at large. I think we all have the power that the Bucks do, but what we need is the solidarity. For designers, technologists and researchers of all disciplines, this is the time to pause, to connect, and to build power for the futures we want to live.

For those of you who may ask, what does this have to do with design, with UX? Let me remind you that the methods we use today for participatory design and research are directly descended from the work of Scandinavian trade unions in the 20th century. Participatory design was developed to empower workers and improve safety and well-being. To divorce our methods from these origins doesn’t do service to anyone.

To be perfectly honest, when I proposed this talk, I envisioned a very geeky methods talk, in which I spoke with objectivity about traditional social science research methods, the legacy of community participation in design research, and some ways that practitioners can shift their methods in order to cultivate relationships within their own communities. And then, to spin this about how good design can change the world!

For anyone anticipating such, sorry, but you’re not going to get that tonight. Instead, I want to reflect on the ways that design and tech, along with the verticals we work across - healthcare, education, draw on resources from their communities and how we might envision a more collaborative way to work in the future.

So what do we do when we can no longer carry on as normal? Like, for real, what does it mean to stand up?

Headline: OHSU ends massive coronavirus study because it underrepresented minorities, oregonlive.com, Aug 27, 2020

You all may have seen the news last week that OHSU, our local teaching and research hospital, announced that it cancelled its 25 million dollar COVID-19 study on the basis that it had failed to recruit a representative sample of folks to participate. As a result, the data it collected was not very useful! Why is this?

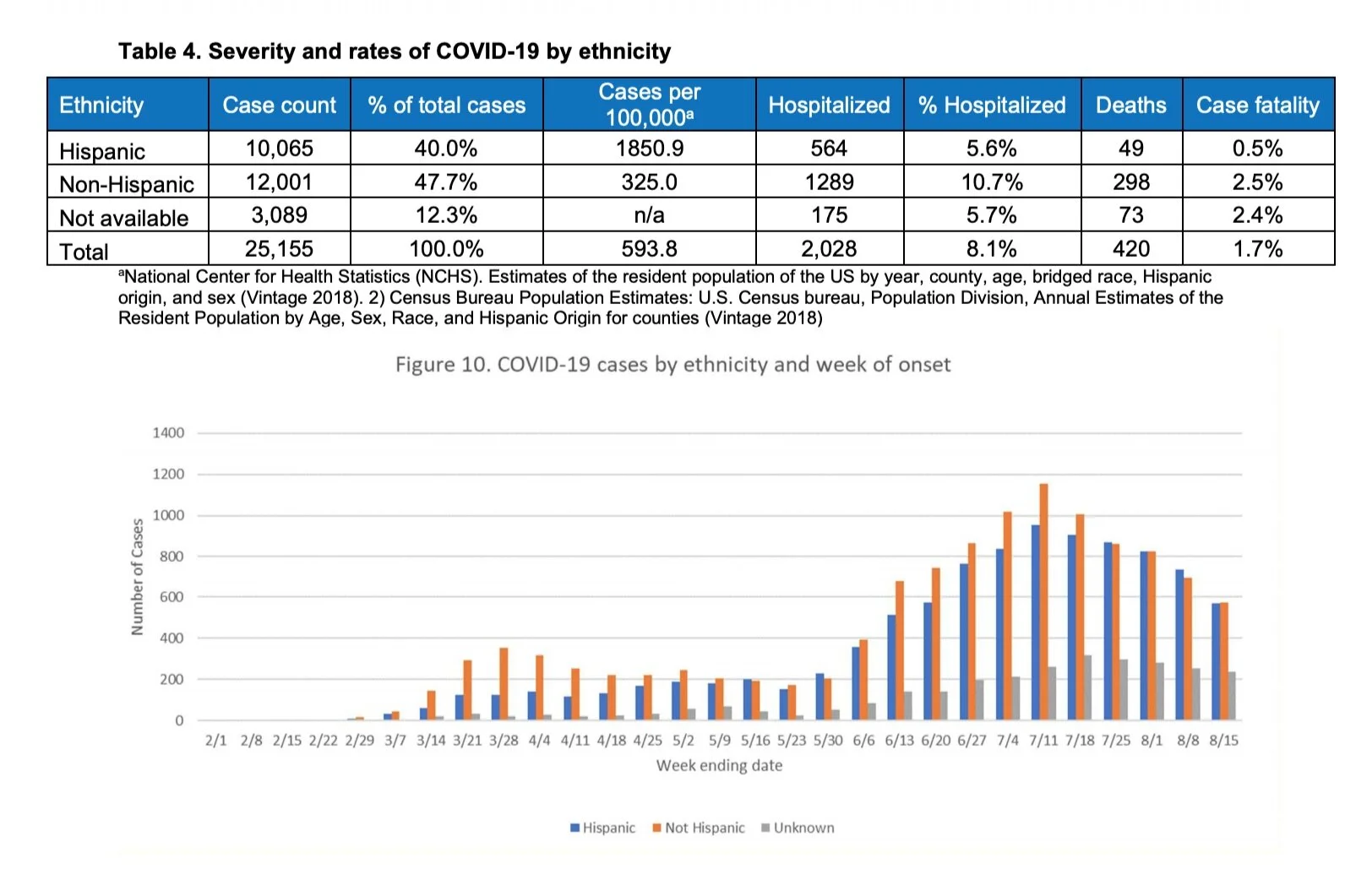

COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted folks of color, both here and Oregon and across the US. As you can see in these tables from the Oregon Health Authority, Hispanic/Latinx folks, who comprise 12 percent of the Oregon population, have accounted for 40 percent of COVID cases. It’s estimated that 90 percent of farm workers in Oregon are Latinx. Think about the relationship between these facts, and what it means for all of us. All of us, in some way or another, rely on the farm workers in our state.

Community organisations, those already working with the populations we’ve outlined here, had a lot of criticism of the methods and practices OHSU employed. For one, their approach was very top-down, and designed in a way that did not build on community connections. Furthermore, one big flaw in the study design is that participants were not originally offered compensation for their time and participation, thus skewing the population who did volunteer towards those who had ample resources.

This is a multi-layered community issue here - we have several communities overlapping here, and no real alignment of goals. We have the global medical research community, eager to use all of its resources. We have a local community here, made up of folks who live in the region. And then we have smaller, more fragmented, but equally important communities within - communities built around shared languages and cultures, neighbourhoods, heritage, shared interests.

One of the things I have not done thus far is provide a singular definition of community, what has been called “a nicely coercive word”. Community can and does mean a lot of things, and the most damaging thing we can do is to take a singular approach to this. The biggest strength of community-centered approaches is that they bring in a diversity of perspectives that strengthens the work, and build more resilient findings and results because of this.

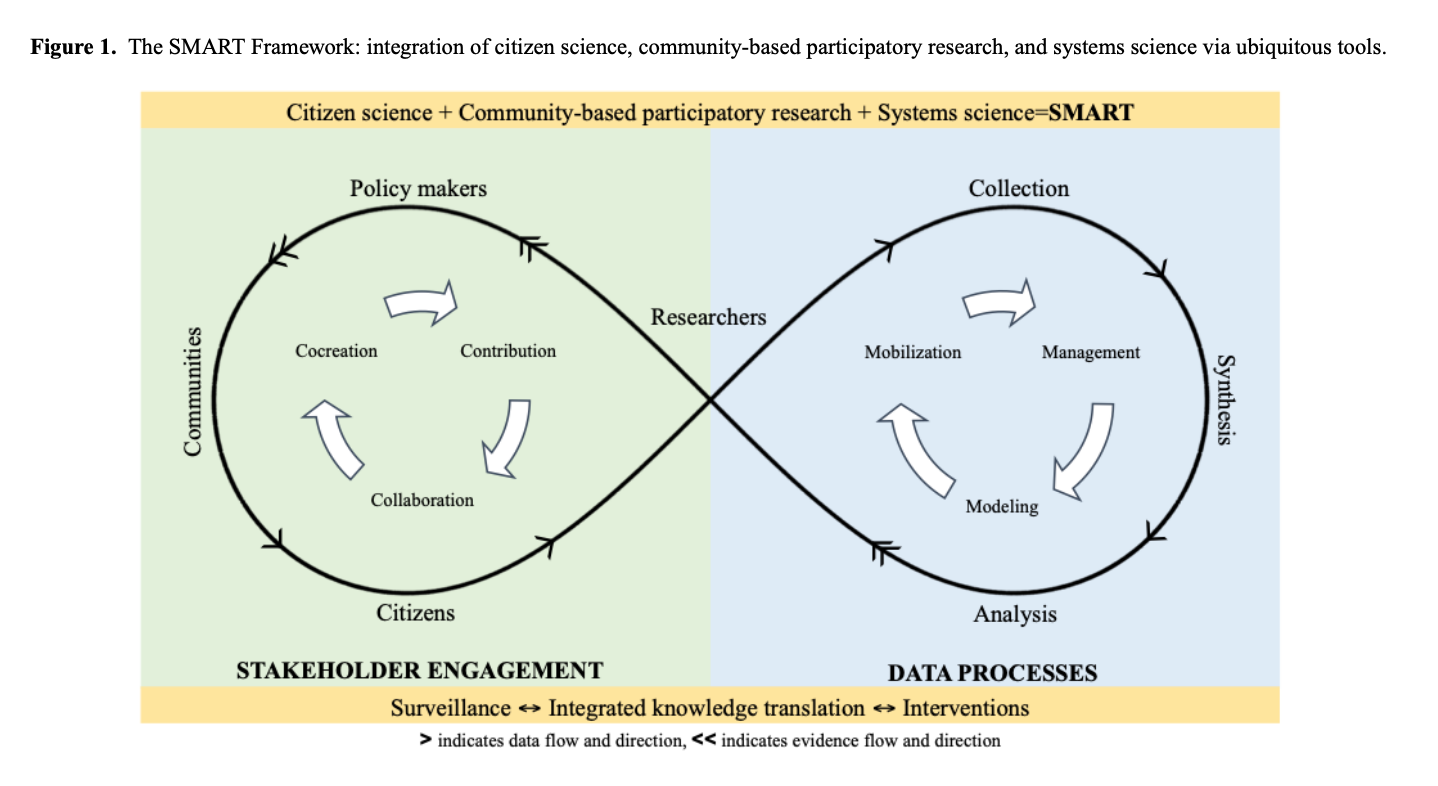

One of many cool models for community-based participatory research, from T.R. Katapally (2019) The SMART Framework: Integration of Citizen Science, Community-Based Participatory Research, and Systems Science for Population Health Science in the Digital Age, https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/8/e14056/pdf

While I’ve discussed biomedical research here, I think the applications can and do apply to us the disciplines we work in. We don’t have to look hard to see examples of the ways in which tech companies have mishandled or neglected the people, places, and communities they serve. We can find one very literal and material example here, on the Oregon Coast, where an environmental advocacy group has initiated a suit against Facebook for abandoning a drilling project and trashing the sea floor.

So how do we move forward?

There are two things that I want to propose here, and neither are complete solutions.

First, I want to draw our awareness towards the way we work and organise ourselves. In the contemporary economy, fewer and fewer of us work in traditional jobs in traditional institutions. Many of us are freelancers or small business operators. Many of us work as subcontractors on projects for companies that don’t actually employ us.

While I would like to fantasize about top-down solutions - what would it mean for tech companies to have community accountability boards? I truly do not see this as a way forward. There are no leaders coming to fix this problem, and it’s one that will impact us all in very de-centralized ways. The antidote, I think, to this huge gap between what our communities truly need and the lack of real solutions provided by corporations and nation states is deceptively simple - small individual actions.

I’m intrigued and inspired by the approaches in Julia Watson’s new book, Lo-Tek, which argues for a design movement building on indigenous philosophy and vernacular infrastructure to generate sustainable, resilient, nature-based technology. I believe that the most meaningful path forward is in building connections around what we share, the natural world being a gateway to all of this.

Perhaps the smallest, most impactful actions we can take are in critically examining our own work.

It’s important to note now, as ever, that design is not neutral, and design thinking is not always a source of good. Moreover, our current moment ( or more accurately, the last decade), has positioned design in a very culturally specific, and I would argue, gate-kept way. Lilly Irani’s work (2015), explores this in depth, and draws on her own experiences as a student at Stanford and a UX designer at Google.

We have spent so much time and rhetorical effort positioning design and design thinking as valuable and creative, and thus positioning the folks who do these jobs in a way that removes them from the actual problems they’ve set about solving.

In our current economy, we’re urged both at personal and institutional levels to devalue, a depersonalise the labor of others, to our supposed gain. We’ve been taught to ignore our bodies, our physical spaces, our histories and culture in order to elevate this work. And I’d argue that it’s made the real work of innovation and collaboration much harder.

What would it mean to approach our work with the belief that it was equally important to any other human work? To view the work of preparing food, keeping essential services running, or caring for children or elders with the same value as we assign to coding and conducting research? What would it mean to make visible, and valuable, the labor made invisible by design and technology? To use artist Jenny Holzer’s truism, what if we all worked under the notion that Everyone’s Work is equally important.

Those who have been at this game for awhile might have some objections to all of this - it is, I suppose, in our best interest in the short term to cast our work as uniquely valuable. Yet, this isn’t a bet I’m willing to make. In order to do the important work, we need to collaborate as equals with the folks who are most impacted by the decisions we make.

Time, of course, is another constraint here. Those who know me know that I’m as impatient as anyone. And yet, the past six months have changed all of our relationship to time.

It struck me that it took sports all over the world shutting down for 48 hours before they took Jacob Blake’s handcuffs off in the hospital in Kenosha.

Building real relationships and partnerships takes time. Changing our approaches takes time. And yet, at the same time, the decade or so I’ve spent in this business has shown a lot of short-term gain and long term stasis.

We need radical, imaginative, and adaptive approaches to do the work we need the most. The future is here. Let’s fight for it.